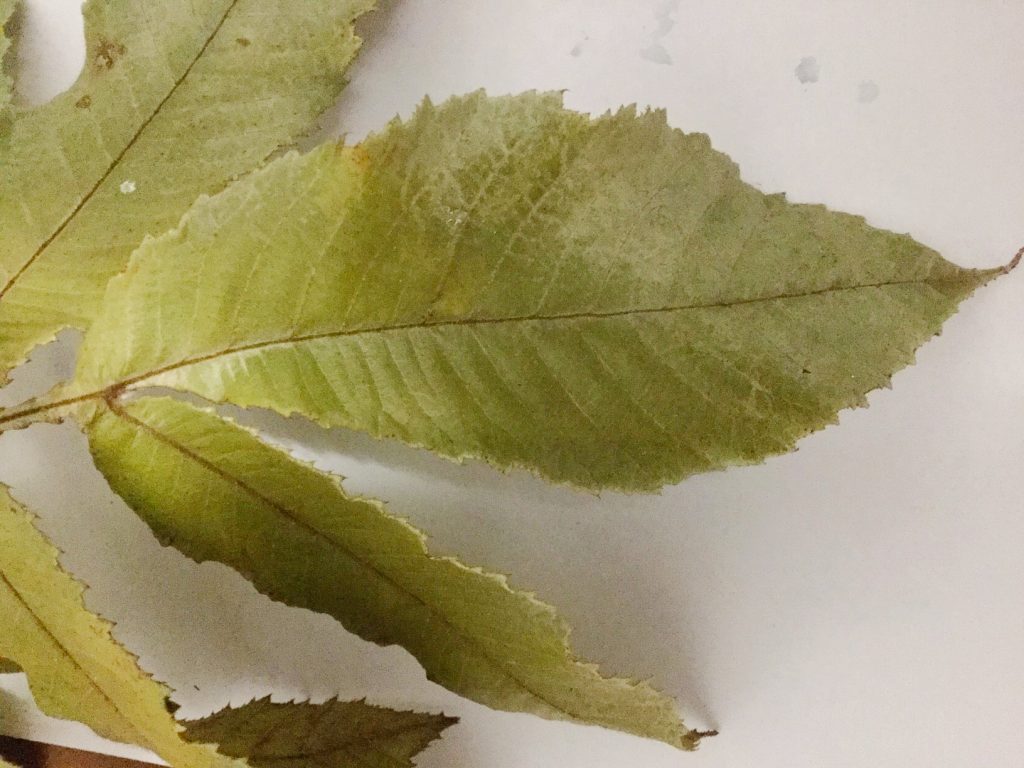

It seems appropriate that during this month of Christmas we feature an evergreen conifer as our tree of the month. The Black Pine (Prumnopitys amara). This species is widely distributed in north-east Queensland as well as New Guinea and Indonesia. It can grow to 60m and has a frequently dark to blackish trunk with scattered cracks. Mature leaves are long and narrow with a distinct groove along the mid-vein on the upper surface. The species name “amara” is from the latin word for bitter and refers to the fact that the leaves, if chewed, are initially sweet tasting but then turn bitter.

Photo by Peter Woodard; Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

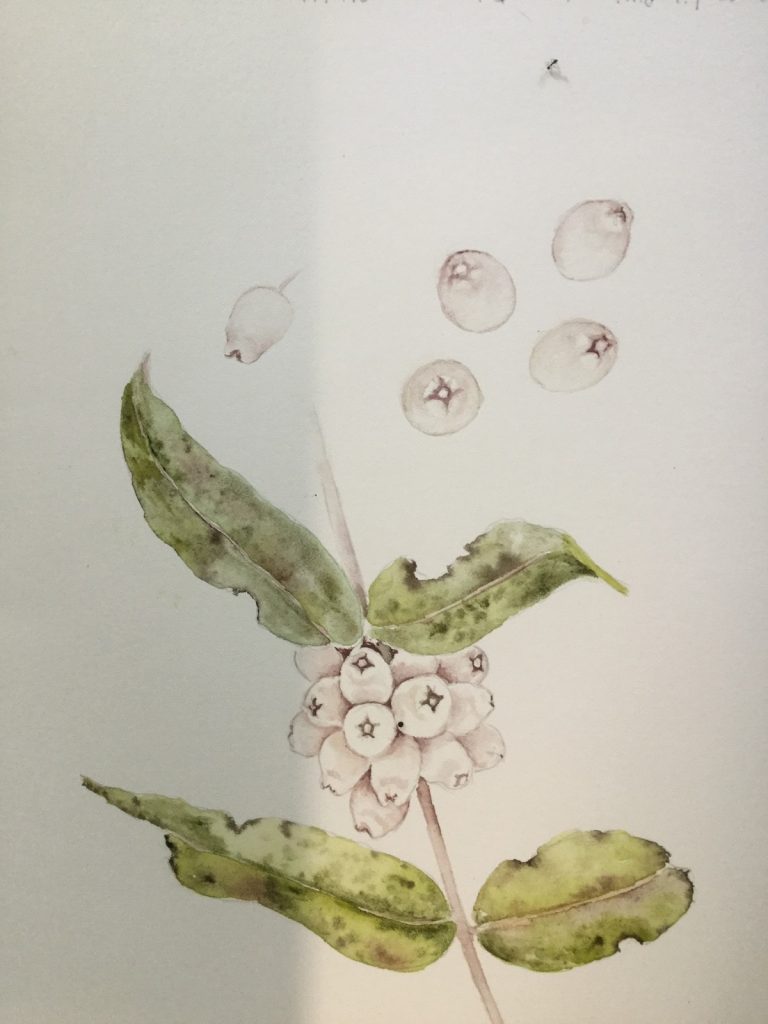

None of these features are easy to distinguish in the field, but luckily the fruit are very easily recognised scattered on the ground along walking tracks. They are bright red and globular (20-25mm wide) with a shallow flesh around a hard gloubular seed. Fruit can be found on the forest floor from December to February. They are eaten by Cassowaries, and several species of rainforest rat.

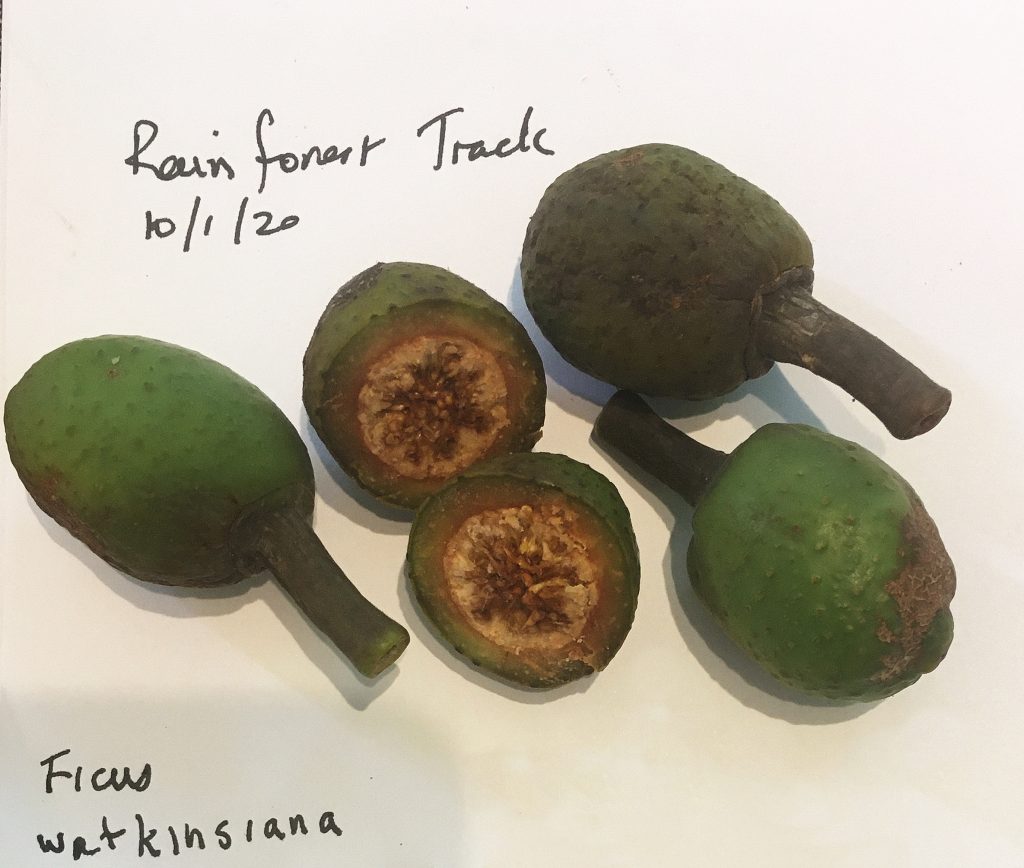

Black Pine nuts are one of about four species of rainforest seeds regularly that were used (and relied on) on by rainforest aborigines as a source of carbohydrates. While some of the seeds required lengthy preparation to leach out toxins and bitter chemicals, Black Pine seeds, could simply be collected and cooked for thiry minutes in a grond oven and then cracked open to reveal the tasty kernels which were then pulverised between two stones.

The timber from the Black Pine is used in New Guinea and Indonesia for general building purposes as well as funiture including butter churns.

Other conifers around Paluma

Conifers belong to a group of seed-bearing plants (including Cycads and Ginkos) in which the seed is not enclosed in and ovary (Gymnosperms – meaning naked seed). The seeds of conifers (Pines and relatives) are borne within cones. Australia has several conifers that are endemic (found only in Australia) and one which is considered to be a “living fossil” (Wollemi Pine).

The Black Pine is one of only a few naturally occurring rainforest conifers in the Paluma region. Two others that can be potentially (but not commonly) seen are “Plum Pines” or Podocarps (Podocarpus grayae and Podocarpus elatus). Both are called Brown Pine and both are endemic to Australia. While not strictly a rainforest pine the Hoop Pine (Araucaria cunninghami) can also be seen naturally on the slopes down to the coast along the range road, and there are several large specimens that have been planted out around the village. It is not restricted to rainforests, and is common around the rocky coast of Magnetic Island.

There are other species of native pine that don’t naturally occur in Paluma but that have been planted out around the village. These include a small Bunya Pine (Araucaria bidwilli) around the first corner of Smith Crescent and a Kauri pine (probably Agathis microstachya*) behind the Paluma Environmental Education Centre. Two small potted native “Christmas trees” adjacent to the the Community hall include one conifer naturally found only in the mountains west of Mossman (Mt Spurgeon pine, Prumnopitys ladei) and a variety of casuarina (not a conifer) called the Daintree Pine (Gymnostroma australianum).

Text and photos (unless indicated) by Jamie Oliver

*Note: the Kauri pine behind PEEC is, on closer inspection, most likely to be Agathis robusta. It is distinguised by its smooth bark with thin flakes. – Jamie