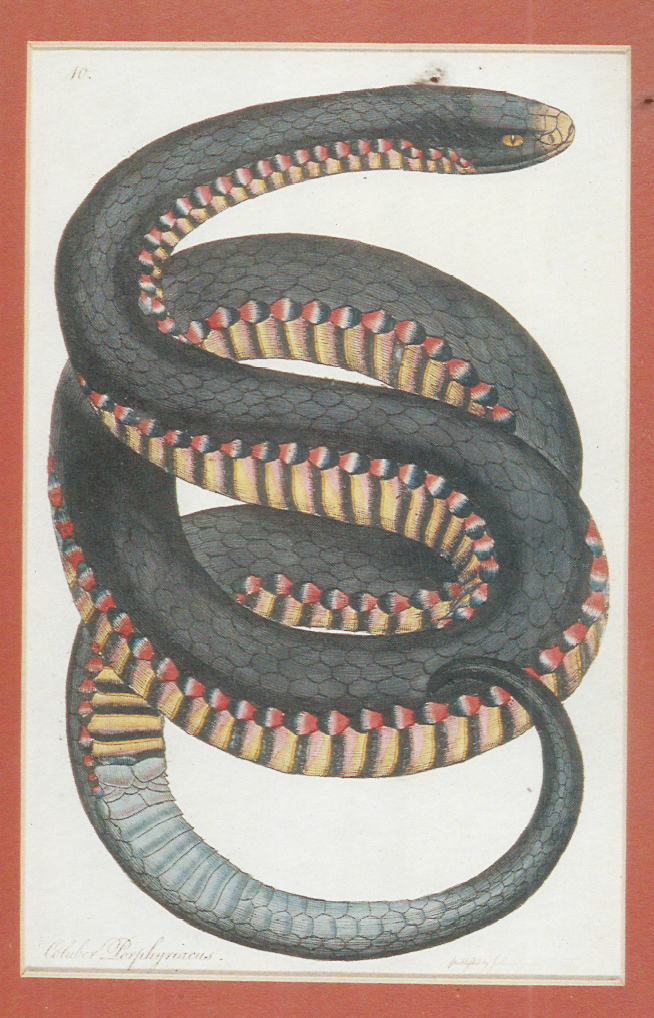

Red-bellied Black Snake (Pseudechis porphyriacus)

Some recent, and unexpected encounters with Red-bellied (or Common) Black Snakes have prompted me (Colwyn Campbell) to write this article about the slithery reptile. I regularly meet these creatures in my garden and whilst out walking. My most recent encounter was last week at 7.30 in the morning after a night of heavy rain.

I was sweeping leaves off the front veranda and had left the door open so that Flossie (my dog) could follow me out. Becoming aware of activity behind me I turned to see, between me and the door, Flossie engaged in a vigorous pas de deux with a very large red-bellied black snake. Without thinking, I used the broom to drag Flossie close enough to grab her by the collar and throw her inside the house, while at the same time trying to fend off the snake and foil its apparent intention of entering the house. I then leapt inside and slammed the door. Poor thing – it probably only needed a warm, dry place to escape from the cold and rain-sodden garden. But I didn’t want it inside my house! I watched it coil up near my firewood box, then promptly rang my neighbour (Len Cook) who sent the snake on its way by turning the hose on it. This is the largest red-bellied black snake I have seen in my area so naturally, I am concerned that Flossie does not meet up with it again.

The red-bellied black snake is so much part of the Paluma rainforest environment that most of us take its presence for granted. Gardeners know to make a few thrusts with a rake to move snoozing serpents away before starting to weed the garden, but what do we really know about these beautiful (but to some, evil and rather terrifying) creatures?

The red-bellied black snake is a member of the Elapidae Family – venomous snakes with fixed poison fangs at the front of the upper jaw. They occur mostly in the tropics, however the red-bellied black snake ranges through much of south-eastern Australia and up to the Atherton Tableland, inhabiting well-watered areas such as woodlands, swamps, creeks, river banks – and Paluma gardens. Its preferred diet is frogs and small lizards, but fish and small mammals may also be included on the menu. A handsome creature, growing to an average of 1.25 metres, the snake’s sleek, glossy black scales shimmer on the upper surface, while the underbelly can vary from a brilliant red to a pale, creamy pink.

Although the red-bellied black snake’s venom is capable of causing significant illness, fatalities in humans are rare, its bite being less venomous than other Australian elapids, such as the king brown snake or taipan. The venom contains neurotoxins, myotoxins, coagulants and has haemolytic properties. Fortunately, the red-bellied black snake is not an aggressive species and will move out of the way rather than face an unpleasant encounter. When provoked, it will assume a striking stance, hiss loudly and flatten the neck and body in a display that is mostly bluff.

That Flossie has not been bitten during the course of her many confrontations with black snakes is proof to me of their docile nature.

Snakes entered Australia millions of years ago from Asia, probably when the continental land masses were still joined. Two main groups of Elapids developed – one group comprised small nocturnal species with specialized feeding habits; and the other group, larger snakes, diurnal (active by day) and with more general diets. This group includes some of the deadliest snakes in the world: brown snakes, black snakes and taipans.

Live-bearing arose in two different lineages of Australian elapids. In one lineage, only a single species is viviparous: the common red-bellied black snake. It is alone among its closest relatives in bearing live young and because of this was able to expand the range of the genus into cooler, south-eastern parts of the country, whereas most egg-laying elapids such as taipans and king brown snakes, are found in warmer or tropical regions.

In bearing live young the female has the advantage of a shorter pregnancy. Eggs retained inside the mother’s body are kept warmer and develop faster than eggs laid in the earth, where in cold climates a low soil temperature impedes development of the embryo, even to the extent of preventing hatching before the arrival of the frosts of autumn. Live bearing benefits the young: enabling them to be born much earlier in the season, thus allowing them to feed and find shelter before the colder weather arrives. The baby snakes are born in a clutch of between ten and twenty, each encased in an amniotic sac from which they emerge within a few minutes ready to fend for themselves.

Black snakes like to maintain a body temperature close to 30 degrees Celsius. Many factors will determine how quickly a snake heats up: the intensity of solar radiation, wind, air temperature and the amount of the snake’s surface that is exposed to the sun. They can regulate their temperature by selecting a warm or cool position to lie, often by moving only a few centimetres, from lawn to beneath a shrub, for example. The snake can position its body so that only a small part is exposed but the warmed blood will carry heat to the rest of the body. If food is scarce, the snake benefits by being inactive and cool rather than expending energy and heat by hunting.

In spring, black snakes emerge and bask in the morning, heating up rapidly. They maintain their optimum body temperature all day even though the air temperature may drop below 20 degrees. In summer however, they generally do not bask, even if the morning is cool and their body temperature is quite low. Rather than heat up immediately they choose to remain cooler. Black snakes are actually cooler when the weather is hotter.

Pregnant females bask longer than non-pregnant females as warmth accelerates development of the embryos and is advantageous to both the mother and the young. An interesting observation is made by herpetologist Rick Shine (whose excellent book Australian Snakes: A Natural History, I have delved into for most of this information regarding black snakes). He describes the gathering together in summer of small groups, of two to six pregnant females when near to giving birth. They share a common night-time retreat, usually a burrow, and emerge together in the morning to bask. Female black snakes in late pregnancy do not feed so they remain in the vicinity of their burrow for weeks.

Although tending not to roam far from their own territory during the year, males in the spring mating season may travel up to 1 km in a day in search of a female. That is when you are most likely to come across one on the Paluma walking tracks!

Snakes have an undeservedly bad reputation, starting from the Biblical serpent who tempted Eve, to the wicked Mrs Black Snake who menaced Snugglepot and Cuddlepie. Other cultures have revered the snake and for many it was regarded as a symbol of knowledge and wisdom. Next time you come across a red-bellied black snake in your garden, pause and admire it for the beautiful and complex creature it is.

Article by Colwyn Campbell

References & More Information:

Rick Shine – Australian Snakes: A Natural History and Graeme Gow – Complete Guide to Australian Snakes.

(Image reproduced from Zoology and Botany of New Holland (1794) from an article on https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red-bellied_black_snake).