by Linda Venn

It should be noted here that I have not accessed court documents but have reconstructed the arguments as best I can from the lengthy and detailed newspaper reports of the day. Accessing the court records is another project altogether.

This instalment focuses on the first day of the court case against Charles Henry Edmonds, “charged with having attempted to steal £391 19s. 5d, and with having at the time being armed with a dangerous weapon – a shot gun”. (Daily Standard, Brisbane, Wednesday 30th December 1931, p. 15) Plain Clothes Detective, William John Gooch, was first to give evidence on Day One of the hearing (Monday 28th December), followed by Patrick James Rynne, a police Constable stationed at Ingham. We will come back to their evidence later. First, let us hear some of the testimony of Constable Leonard Edward O’Brien, who gave evidence on Day 2 (Tuesday 29th December).

O’Brien was based at West End Police Station. He had been the armed escort to Mt Spec once before and had known Edmonds for seven years. On 9th December, O’Brien had met the Main Roads Paymaster, Michael Killoran, at the Commonwealth Bank of Australia in Townsville, presumably in Flinders Street. At 8:30am, they left for Mt Spec via rail motor. O’Brien was armed with a Police service revolver and rifle, both loaded. Killoran was also loaded with a revolver. When they arrived at Moongabulla Railway Station (Ollera Creek) at 10:30am, they were met by a Main Roads driver, Harry Stewart in a utility truck. The bag containing the money was placed in the bottom of the truck. The three men sat in the seat of the ute, Stewart as driver, Killoran in the middle and O’Brien on the passenger side. They called first at the pipeworks on Ollera Creek, where Killoran paid two employees.

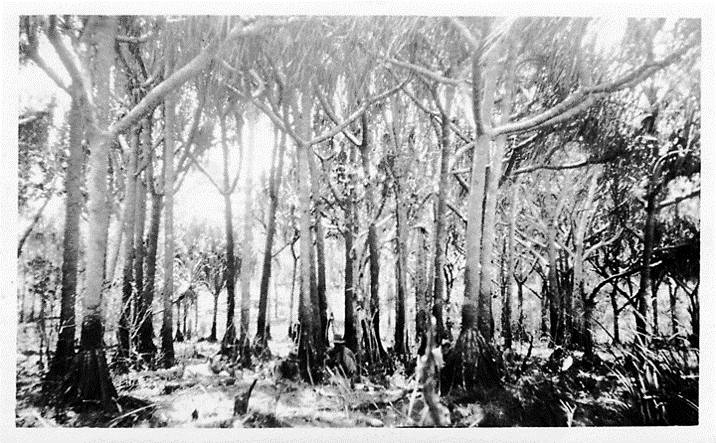

Continuing along Mt. Spec Road, they passed through Tealby’s yard, then on for a further mile and a half where a log lay across the road at a bend. The log was later measured at thirteen feet. The tree looked as if it fallen over in recent wet weather. Stewart drove up close to the log and O’Brien jumped out to inspect it. They had not seen anyone up until then. O’Brien had holstered his revolver, but the rifle was still in the truck. He didn’t have time to move the log, being distracted by “a voice in the distance”, which called out “Put them up!” O’Brien then noticed a man hiding “in some bushes about 15 yards off the road, and slightly to the rear.” Much of the prosecuation’s case relied on O’Brien’s description and identification of the perpetrator. This man was wearing “an old brown coloured hat” and his face was covered “with a piece of material similar to a handkerchief”. He was also wearing “a dirty jacket, similar to a shirt coat or pyjama coat, which was hanging outside his trousers. There appeared to be a bulk in the breast of his coat”. Immediately after calling out for the armed party to surrender, the bandit fired a shot. Stewart got out on the driver’s side, while Killoran fell out of the other side, slightly wounded to the head. O’Brien could not see what kind of gun it was. O’Brien “took cover from behind the right hand mud guard and fired at the man with his revolver, at which the man returned fire, the shot hitting the car.” O’Brien then fired two more shots in quick succession, after which the bandit left the cover of the bushes and headed for the hills. Grabbing his rifle from the ute, O’Brien fired three more shots at the man, none of which appeared to have any effect, and followed him for about 20 yards before Stewart called him back. The bandit was running away from the Mt Spec Road, through thick undergrowth, and was making for a gully that ran between the crime scene and the mountain. A total of eight shots had been fired, two by the bandit and six by Constable O’Brien. Returning to the truck, he found Killoran wounded, “a fresh wound on his head which was bleeding and also found a hole in his hat which corresponded with the wound in his head. The wound appeared to have been made by a pellet.” O’Brien did not examine the utility truck for any damage. After he removed the log from the track, they proceeded to the Main Roads camp at the bottom of the range. Camp No. 1 had telephone communications, so contact was quickly made with Main Roads and Police Inspector Loch in Townsville. Having handed over the payroll, O’Brien organised a search party and travelled back to the scene of the crime in another Main Roads vehicle, “arriving there shortly after mid-day and remaining there till dark.” Following the course taken by the bandit, he found an old brown hat which he later gave to Detective Gooch. O’Brien also found some wads from shot gun cartridges. He was able to track where the bandit had run through the undergrowth and stated that he had had “a clear view of the defendant when he was running away for a couple of yards” and again when he left his barricade, “in full view for at least 22 yards.” (Townsville Daily Bulletin, Wednesday 30th December 1931, p. 11)

Later in the afternoon, Police reinforcements arrived. Detective Senior-Sergeant O’Driscoll, Detective Gooch and Plain Clothes Constable Raetz arrived from Townsville; Constable Rynne and Acting-Sergeant McDonald arrived from Ingham. Two Aboriginal trackers came too. Before continuing with O’Brien’s testimony, we will look next at the evidence given by Gooch and Rynne. (See Townsville Daily Bulletin, Tuesday 29th December 1931, p. 5)