QUANDONG

Elaeocarpus grandis, synonymous with Elaeocarpus angustifolius

Most of you will be familiar with the Quandong’s moss-covered buttressed roots projecting out from the forest onto the edges of walking tracks. Many of these magnificent trees may be seen in the Paluma rainforest with some especially good specimens along the Witt’s Lookout track. The Quandong, a tree emblematic of tropical rainforest is also known as Blue Quandong, Silver Quandong, Blueberry Ash and Blueberry Fig.

A pioneering tree, the Quandong can grow to five or six metres high in just a few years, eventually reaching a height of up to 35 metres. A strong identifying feature are the buttresses with vertically flat, visible roots, so large in some instances that they are capable of sheltering a cassowary. Moss usually covers the trunk and roots so it is difficult to readily see the nature of the bark, but the cut timber is hard and white and highly regarded as a cabinet timber.

Flowering occurs between October and March, the softly fragranced flowers, growing in racemes from axils or on branches are usually high in the tree and difficult to see. They can be green, white or cream with tiny petals about 5 mm long.

Fruiting can occur at any month. You can sometimes find the blue to purple fruit lying among the fallen leaves on the rainforest tracks. Their colour is often enhanced with a metallic sheen. The fruit is a drupe (fleshy with one or more seeds inside) and can be anything from the size of a small grape to that of a golf ball. The fruit is edible and has a higher Vitamin C content than oranges. It is best eaten when slightly over-ripe or it can taste bitter. It can be used in jams or pickles. Many bird species eat the fruit which is also eaten by Bush Rats, Spectacled Flying Foxes and Musky Rat Kangaroos.

The leaves of the Quandong are glossy and about 80 to 150 mm long. As it ages the leaf turns a bright red before dropping. Many can be seen at any time along the walking tracks.

The Quandong was highly valued by rainforest Aboriginal people. The fruit was recognised for its medicinal properties and as a food source. They would also make an edible paste from the ripe fruit. Shields were made from the large buttress roots.

Look for these spectacular trees next time you take a walk along one of the rainforest tracks.

Text & Photos by Colwyn Campbell

Glochidion hylandii is a shrub or small tree growing to a height of up to 12 metres, usually to be found on the edges of rainforests or in revegetation areas as a pioneer tree. The leaves are simple, elliptic and between 30 and 150 mm long with clearly defined veins. Upper surfaces are smooth, or sparsely covered with fine hair while the undersurface is slightly waxy with fine brown hairs. Flowers, growing in the leaf axils are inconspicuous, being only 2 or 3 mm with 6 green sepals and no petals.

Glochidion hylandii is a shrub or small tree growing to a height of up to 12 metres, usually to be found on the edges of rainforests or in revegetation areas as a pioneer tree. The leaves are simple, elliptic and between 30 and 150 mm long with clearly defined veins. Upper surfaces are smooth, or sparsely covered with fine hair while the undersurface is slightly waxy with fine brown hairs. Flowers, growing in the leaf axils are inconspicuous, being only 2 or 3 mm with 6 green sepals and no petals.

Worldwide, there are about 120 species of Sloanea –named for British scientist and collector Hans Sloan, who lived 1660 to 1753. Four species are endemic to Australia with three of these growing in tropical rainforests in Queensland. Sloanea australis is distributed between the Windsor Tableland and Paluma. Several of these trees may be seen on Mount Spec Road near the Sensory Trail at Paluma Environmental Education Centre where they grow among the stand of forest trees bordering the school property.

Worldwide, there are about 120 species of Sloanea –named for British scientist and collector Hans Sloan, who lived 1660 to 1753. Four species are endemic to Australia with three of these growing in tropical rainforests in Queensland. Sloanea australis is distributed between the Windsor Tableland and Paluma. Several of these trees may be seen on Mount Spec Road near the Sensory Trail at Paluma Environmental Education Centre where they grow among the stand of forest trees bordering the school property.

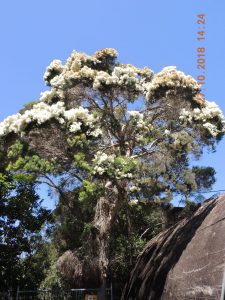

This small evergreen tree grows to a height of 6m to 10m. It is from the myrtle family and is endemic to New South Wales and Queensland. This particular specimen was planted in the early 1990’s (in 1993 or 1994) by long-time Paluma resident Kelly Davis. The trunk of this tree has thick sheets of papery bark. The flowers are a major attractant for bees, butterflies and birds.Unfortunately, the spectacular display of the ‘Snow in Summer’ will not last long; already some of the blooms are browning in the tropical heat.

This small evergreen tree grows to a height of 6m to 10m. It is from the myrtle family and is endemic to New South Wales and Queensland. This particular specimen was planted in the early 1990’s (in 1993 or 1994) by long-time Paluma resident Kelly Davis. The trunk of this tree has thick sheets of papery bark. The flowers are a major attractant for bees, butterflies and birds.Unfortunately, the spectacular display of the ‘Snow in Summer’ will not last long; already some of the blooms are browning in the tropical heat.

Some people liken the smell to sarsaparilla, hence another popular name for this tree. Rainforest Aborigines used the Alphitonia petriei medicinally, probably as a liniment.

Some people liken the smell to sarsaparilla, hence another popular name for this tree. Rainforest Aborigines used the Alphitonia petriei medicinally, probably as a liniment.

is one rainforest tree that can be unmistakably recognised by its bark. The bright red/orange papery bark stands out like a glowing beacon in the surrounding greens of the forest. The flakes of bark are thin, soft and translucent.

is one rainforest tree that can be unmistakably recognised by its bark. The bright red/orange papery bark stands out like a glowing beacon in the surrounding greens of the forest. The flakes of bark are thin, soft and translucent.

When in bloom, usually any time from April through June, the White Hazelwood tree (Simplocos chinchinensis,) is eye-catching crowned with a dense display of fluffy, white flower panicles. The flowers have a delicate fragrance and attract insects and birds. One of these trees is at present (early June) in full bloom and may be seen at the southern gate of the High Ropes course. There are several of these trees scattered around the village and along the sides of the Ridge Road near Paluma. Not all are yet in bloom.

When in bloom, usually any time from April through June, the White Hazelwood tree (Simplocos chinchinensis,) is eye-catching crowned with a dense display of fluffy, white flower panicles. The flowers have a delicate fragrance and attract insects and birds. One of these trees is at present (early June) in full bloom and may be seen at the southern gate of the High Ropes course. There are several of these trees scattered around the village and along the sides of the Ridge Road near Paluma. Not all are yet in bloom.

The Scrub Ironwood is a member of the Myrtaceae family; Genus – Gossia, Species – bidwillii.

The Scrub Ironwood is a member of the Myrtaceae family; Genus – Gossia, Species – bidwillii.