By Andi Cairns

Bryophytes, the collective name for mosses, leafy and thalloid liverworts, and hornworts, are generally small, inconspicuous plants. They are often overlooked but are extraordinarily diverse. Most people will walk past a mossy log in the rainforest without giving it a second glance…but did you know that there could be 5 or more species of bryophytes there? And they aren’t all ‘moss’!

Diversity is particularly high in the rainforests of the Wet Tropics. Of the 950+ species of mosses listed for the Australian continent, over 414 species have been recorded for north-eastern Queensland – almost 45% of the total! They are uncommon on the forest floor as they are quickly covered by fallen leaves, so look for bryophytes on earth banks, rotting logs, rocks, in streams, on the bark of trees and vines and on tree fern trunks (epiphytes), and as tiny communities on the upper surface of leaves (epiphylls).

Characters that separate bryophyte species are often difficult to identify without the aid of a microscope but there are several taxa that are easy to recognise with the naked eye – so for the Bryophytes section we’ll go with ‘5 easy genera’!

1. Leucobryum – moss

Many rotting logs in the Paluma rainforest provide substrate for Leucobryum. The genus takes its name from the Greek leukos = white and bryon = moss. Six species of this white moss have been recorded from the Wet Tropics, of which four may be found at Paluma, growing on tree trunks and roots, dead wood, rocks, and occasionally on soil. Most mosses have leaves that are one cell thick but Leucobryum is an exception. Leaves are up to 3-, sometimes 4-cells thick with small cells containing chloroplasts sandwiched between large, hyaline (clear) cells – which is why Leucobryum looks pale green or whitish compared with other mosses

2. Lopidium – moss

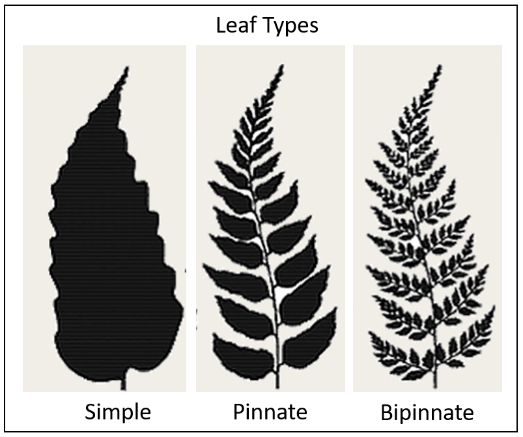

Lopidium grows on saplings and tree trunks and could easily be mistaken for a miniature fern. Fronds can be up to 9 cm long but are often shorter. Unlike most mosses, which have leaves in a spiral arrangement around the stem, Lopidium has leaves that appear flattened in one plane. Australia has two species of Lopidium – L. concinnum and L. struthiopteris. Both are recorded from Paluma.

3. Hampeella – moss

Two species of Hampeella are known from the Wet Tropics – H. pallens, also known from Malesia and Taiwan, and the endemic H. concavifolia. Both species occur in the Paluma rainforest, attached to saplings or twigs (epiphytic), and occasionally growing along leaf margins (epiphylls). Stems of this bright green moss are 3–7cm long, often shorter.

4. Rosulabryum – moss

Rosulabryum is a genus of mosses recorded from most Australian States. Eleven species have been listed for the Wet Tropics but only five species occur in the vicinity of Paluma, growing on tree trunks or on the forest floor, often in large mats. Spirally arranged and usually clustered in a rosette, leaves are quite large (up to 6 mm long) – if you look closely you may see that each leaf has a central midrib (known as a ‘costa’).

McClellands Lookout the central midrib = costa

5. Bazzania – leafy liverwort

A closer look at the ‘mossy’ trunks of trees will reveal they are often not covered with moss at all!

The leafy liverwort Bazzania is common on tree trunks and branches or growing intermixed with mosses such as Leucobryum. Look closely at the log covered with Leucobryum along the H-track. At the lower edge of the log you’ll find a band of Bazzania adnexa. Twenty-nine species of Bazzania have been recorded for the Wet Tropics, many of which occur in the Paluma rainforest. All Bazzania species have two rows of lateral leaves, a row of ventral leaves (underleaves), and fine branchlets with minute leaves arising from the axils of underleaves. The shape and size of the underleaves aid in identification of Bazzania species.

Bazzania sp. covering a tree trunk, Witts Lookout walking track

Bazzania adnexa showing underleaves and fine branchlets with reduced leaves

Bazzania adnexa, one of the many species of Bazzania recorded from Paluma

Found an interesting bryophyte in your garden?

Andi would be happy to identify it!

Contact Andi: andi.cairns@bigpond.com

.jpg?bwg=1585014263)