Members of the Benham family are commemorated in many of our local place names, for example, Benham’s Creek, Mount Benham, Ethel Creek and Ethel Creek Falls, Benham Falls, Benham’s Track (now a road on some maps), Benham’s Lookout (now closed), Cloudy Creek and Cloudy Clearing. Other place names associated with the Benhams are Prospectors Creek (now Hermit Creek) and Hermitville. There may be others, but these will suffice to recognise the long association of this family with the Mount Spec area.

The Misty Mountain

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the open and closed forests around Mount Spec were home to three Aboriginal language and cultural groups. Successful native title claims between 2012 and 2018 have recognised these associations. These applications recognised the claims of each group to traditional homelands. For the Nywaigi People, their country is the Paluma Range and coastal plain between about Rollingstone and Forrest Beach; for the Gugu Badhun People, it is an extensive area going west of the Paluma Range, and for the Gurambilbarra Wulgurukaba People, from the Ross River north to about Rollingstone. The recently registered claim by the Nywaigi people covers about 840 km2 south of Ingham and includes parts of the Charters Towers, Hinchinbrook and Townsville Council areas. It must be acknowledged that when the Benham family moved into this area in the 1880s, they were moving into Nywaigi country as very early European settlers of the Mount Spec area.

The Benham Family arrives in Australia

There were quite a few Benhams. George and Sarah Benham of the English garrison city of Winchester had fifteen children. George (Senior) and eleven of his children migrated to Australia between 1883 and 1900, leaving Sarah (Senior) and four children behind in England. The Benhams who immigrated were:

- Frederick (born 1862, died 1919), Emily (born 1863, died 1909) and Arthur Benham (born 1868, died 1956) arrived in Townsville on the Hereford on 25 August 1883.

- Jesse Benham (born 1866, died 1953) arrived in Townsville in December 1884 on the Roma.

- George (Junior) Benham (born 1865, died 1947) arrived in Brisbane in April 1885 on the SS Merkara

- George (Senior) (born 1830, died 1902), Edwin (born 1871, died 1949) and Sarah (Junior) Benham (born 1870, died 1955) arrived in Brisbane in March 1886 on the SS Dacca.

- Edith (born 1872, died 1952), Marion (born 1874, died 1946) and Ethel Benham (born 1877, died 1972) arrived in Brisbane on 4 March 1889 on the SS Jumna.

- Not to be left behind in England, the youngest son, Henry Benham (born 1882, died 1967), jumped ship as a merchant seaman in Brisbane about 1900.

I found no immigration record for Henry (not surprising if he was a deserter), nor for Jesse, who may have come out as either a Free Passenger (the British Government paid his whole fare) or as a Remittance Passenger (the fare was partly paid by the Government and the rest was sponsored by a friend or relative already in the colony). The other nine Benhams are listed in the State Archives as Assisted Passengers, however the copy of Emily’s “contract Ticket” shows she was a Free Passenger (as were most young single woman at the time) (Lee Digweed & Marilyn Hammond, p. 33). Assisted Passengers had part of their fare paid by the Government and the passenger paid the rest (£4 for each passenger under twelve years of age and £8 for those aged over twelve). Both Assisted and Remittance Passengers were contracted to pay the Queensland Government back within a year. On receipt of this repayment, adults would receive a non-transferable land grant of forty acres. (Queensland State Archives, Index to Registers of Immigrant Ships’ Arrivals 1848-1912 Series ID 13086, p. 211; Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser, Tuesday 8 March 1870, p. 4.) While I don’t know if any of the Benhams claimed their land grant, I do know that of the twelve Benhams who migrated to in Australia between 1883 and 1900, at least six spent time in the Mount Spec-Paluma area over a period spanning almost seven decades to the 1950s. (Digweed & Hammond 1986, pp.5,7,11,16) In chronological order of their age, these six siblings were Frederick James, Emily, Jesse Edward, Arthur Ernest, Edwin Henry and Ethel Amy Benham.

The Benham Brothers and Tin Mining

The Benhams were involved with mining around the Mount Spec area from the very beginning. Four Benham brothers – Frederick, Jesse, Arthur and Edwin, along with brother-in-law Arthur Dyer – are recorded as having held leases on the Kangaroo Hills Mining Field. The official date of discovery of alluvial tin at Running River and many of the creeks in the Kangaroo Hills Mineral Field is now given as 1875. (Bureau of Mineral Resources 1965, p. 20; Herbert River Express 18 November 1982; Pike 1960, p.38) Digweed and Hammond give credit to Fred, Arthur and Edwin for the discovery of lode tin in 1889 at Mount Brown (near the eventual township of Ewan near the junction of Running River with the Burdekin). (Digweed & Hammond 1986, pp. 11,21). Members of the Benham family held mining claims and leases from September 1892, the date of Fred’s first recorded mining lease, the Lady Susan Starkey mine near Bosworth’s Hotel between Hidden Valley and Mount Spec. I believe this is the location of the township recalled as Mount Benham, today known locally as “the Old Place”. Adjacent to the World Heritage Area locked gate on Benham’s Track at the head of Hidden Valley you can see the remains of the 5-head stamper battery. On the other side of the gravel track are some foundations and exotic trees that mark the site of the hotel. There was quite a settlement at Mount Benham in 1892, as the excerpts below from an 1892 article in the North Queensland Register attest. As well as being a miner, Fred and his wife Annie were at times storekeepers at Cloudy Clearing (Paluma) and Prospector’s Creek (now known as Hermit Creek, near Mount Spec itself). (North Queensland Register 12 January 1980; Digweed & Hammond 1986)

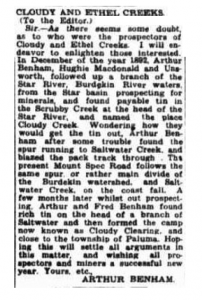

Arthur, with partners MacDonald and Unsworth, is credited with finding alluvial tin at Cloudy Creek at the head of the Star River in December 1892, although his first recorded claim was not registered until July 1894 at Mount Benham. (Digweed and Hammond, pp. 21, 103) The Queenslander in 1891 noted that little notice had been taken of this new tinfield, where “at Mt Benham (twenty miles east of Kangaroo Hills) 150 men are doing very well [in] country covered with dense scrub”. (Queenslander 26 September 1891) By November 1891, machinery had been ordered for the Pineapple lode. (Queenslander 28 November 1891) The 1892 Mining Warden’s Annual Report mentioned old and new tin camps in the ranges at the head of Running River and branches of the Star. The area employed 130 miners sluicing in deep trenching and gullies. Some shafts had also been dug. (Annual Report of the Department of Mines 1892, p. 94) In 1894, the Annual Report highlighted the abundance of tin within the ranges of the Kangaroo Hills Field:

During the year 1894 the headwaters of the Star River have been prospected and worked with the result of producing about half of the tin got on the whole field. This place known as Cloudy Creek is on the headwaters of the Star and Running Rivers and Saltwater [now Crystal] Creek, a distance of about ten miles from the coast, and a height of 2900 feet above high water. The workings are all in dense scrub. (Annual Report of the Department of Mines 1894, pp. 105-106)

Problems with Access

Transport in the broken and heavily timbered country was always a problem, and expensive at six to nine pounds per ton. (Annual Report of the Department of Mines 1901, p. 90; North Queensland Herald 12 April 1902) Stories of crushing batteries carried in through ‘the jungle’ in pieces on men’s backs passed into local folklore. (Herbert River Express 20 November 1982) In 1902, the miners at Mount Spec asked the government for a mail service but were told their service to Hidden Valley (fourteen miles away) was sufficient. Mail was brought to Mount Spec from Hidden Valley by the occasional visitor or traveller. The thirty to forty men at Mount Spec were living in tents and were existing on corned or tinned meat, bread and tea. Some fresh meat and other stores were delivered to the mining field by Jack Hood and “Bullocky Tom” Andrews from Mutarnee, and miners tried growing their own fresh vegetables. (North Queensland Herald 12 April 1902)

Early prospectors like the Benhams opened foot and pack tracks into the forest from the west and down the coastal face of the ranges in the 1880s and 1890s. One of these tracks was Benham’s Track. Benham’s Track today, from the Paluma Dam to Hidden Valley, follows part of the original Benham’s Track, the first portion of which was cut from today’s Hidden Valley into Mount Spec in the 1890s. The next section connected Mount Spec with the Benham brothers’ mining activities in Cloudy Clearing. The drier section of Benham’s Track was later improved to wagon road standard by the Gorringe brothers. This was one of few roads of that calibre in the area. (Herbert River Express 20 November 1982)

Arthur Benham first used teamster William James to transport his bagged tin to Townsville down through Running River and back over the range at The Pinnacles. This was the easiest access to and from Townsville, via Thornton’s Gap [Hervey’s Range]. (Shepherd in Burla n.d., p. 2) This road was very steep, and required a large log tied to the back of the wagon to act as as a brake. (Digweed & Hammond 1986, p.103) The Benham brothers moved between “the scrub” and the drier country to the west of Mount Spec, as further discoveries were made. In 1899, the Benham brothers were working in drier country, as the report of a visitor to the Kallanda Tin Mines in November shows.

North Queensland Register, Wednesday 17 August 1892, page 21

North Queensland Register , Monday 11 December 1899, page 29

Problems raising Capital

Miners and mining capital for the Mount Spec – Cloudy Clearing (Paluma) area came first from Ravenswood and Charters Towers, with prospectors following Burdekin River tributaries like the Star and Running Rivers up to their source. (Annual Report of the Department of Mines 1883, p. 178; Shepherd in Burla n.d., p. 2) Gold discoveries at Cape River (1867), Ravenswood (1868) and Charters Towers (1871) had provided further impetus for prospecting over the whole district. (Levingston 1971, p. 1) Townsville and Ingham were vying for the trade of the new Kangaroo Hills Mining Field, but both towns could only be accessed over bad roads, each with a steep ‘jump-up’ on the coastal escarpment to the mining field. (Shepherd in Burla n.d., pp. 2, 7, 9; Herbert River Express, 23 November 1982) Ingham was closer to Mount Spec, but the tracks from there were steep and hard to maintain. The Benham family history clearly shows the early links between Mount Spec-Paluma and Townsville, Ingham and especially Charters Towers, with many of the Benham family eventually making their homes and being buried in ‘the Towers’. (Digweed & Hammond 1986)

Convincing shareholders to invest in mines with such access difficulties was not easy. In 1900, the Mount Spec Tin Mines Company erected a five-head, steam-powered battery at the Mount Spec Mine, nine miles from Hidden Valley. Bringing in the five-head battery took six weeks over Hervey’s Range via Waverley Tin Mines. (North Queensland Herald, 12 April 1902) This battery was capable of treating ten tons of lode ore a day. The 1901 Annual Report of the Department of Mines commented on the expense of getting the battery, with all its plant and machinery, on-site:

Little has been done in development during the last twelve months, but the company may be congratulated on the pluck and energy they have shown in bringing machinery on the ground in face of great difficulties and heavy outlay. (p. 89) Heavy water prevented the working of a promising chute of ore to a greater depth than seventy feet unless improved pumping machinery was brought in. (Annual Report of the Department of Mines 1902, p.82)

This venture survived only a few years, with the removal of the battery to Mount Brown near Ewan in the drier open forest being foreshadowed in the 1902 Annual Report. (p. 85) No production was recorded by this company after the machinery was removed. (Robert Brown, 28 July 1984, Interview)

Apart from such short-lived companies, most mining ventures around Mount Spec-Paluma appear to have been small affairs, consisting of single ‘scratchers’, family partnerships, or small groups of men. Around 1905, there was another small rush in alluvial tin at Cloudy Creek, fifteen miles from both Ollera Creek and Hidden Valley. Up to fifty men were established there with a tramway of 200 to 300 yards running from the workings to a dam. The workings were at the 3000 feet level and loam carrying tin had been excavated from the surface to a depth of thirty-six feet. Another minor rush occurred in dense scrub country around Ethel Creek (named for sister Ethel Benham). “Settlement” there consisted of fourteen huts. (Robert (Bob) Burla, Notes supplied to Digweed & Hammond)

Benham’s Track

Arthur Benham lived long enough to see a road down the coastal escarpment from Cloudy Clearing to Townsville eventually put through as The Mount Spec Tourist Road, more than thirty years after the mining of tin in the district had peaked. In a Letter to the Editor of the Townsville Daily Bulletin in January 1935, Arthur Benham claimed credit for continuing his track from Cloudy Clearing down to the coast, connecting with Bullocky Tom’s Track at the ‘Mango Tree’. Bob Shepherd (Herbert River Express 20 November 1982) gave the location of the ‘Mango Tree’ as being on the present range road to Paluma, but a ‘Mango Tree’ is shown on a 1977 Parish map as being on Bullocky Tom’s Track at the junction of Big Crystal Creek and Nolan’s Gully. This map also shows a track connecting the ‘Mango Tree’ with ‘The Saddle’ on the range road above the Little Crystal Creek bridge. (Department of Mapping & Surveying January 1977, Parish of Waterview Map) The alignment of the then newly-completed (now the present heritage-listed) Mount Spec Road was claimed by Arthur Benham to largely follow the coastal section of his Benham’s Track. Construction of the Mount Spec (Tourist) Road is another story. Suffice to say, its absence for much of the Benhams’ working lives made life difficult, as this excerpt from the 1902 report by Government geologist Cameron makes clear:

The coast range forms the boundary of the mineral country on the north-east. It presents an abrupt front to the sea at a distance of from 8 to 30 miles from it, and has a general elevation of nearly 2,000 above it. It is at present impracticable for vehicles wherever it is approached from the mouth of the Herbert River, and all conveyance to the field from the coast at this point has to be undertaken by means of horses. (Queensland Government Mining Journal 15 January 1902, p. 21)

The topography of this area has always had access difficulties. Despite the completion in 1935 of the Mount Spec Road as far as Cloudy Clearing (Paluma), a mule team was still being used in the 1940s and 1950s on the mail service from Stone River to Hidden Valley. (Herbert River Express 23 November 1982; North Queensland Register 20 September 1980).

Townsville Daily Bulletin, Tuesday 8 January 1935, page 9

Problems with Working Conditions

Bad roads, or no roads, were only one of the difficulties miners like the Benhams faced in living and working in our forests. In his recent post Nature Notes, Roy Mackay notes that it is many years now since Paluma has had its average rainfall. This was not seemingly the case for the Benhams, who endured working conditions in the rainforest that were difficult and sometimes dangerous. The 1893 Annual Report of the Department of Mines noted:

At Mount Benham the mining is all in dense tropical scrub, which adds terribly to the difficulty of prospecting and mining, and also of getting the tin away from the claims. (Annual Report of the Department of Mines 1893, p. 85)

Miners also suffered plagues of fleas, ticks, leeches and snakes. (North Queensland Herald, 12 April 1902) In event of an injury, medical help was a long way off. Benhams’ neighbour Jack Johnstone had to walk himself out of the scrub with an arm shattered in a shotgun accident. (Herbert River Express, 20 November 1982) In March 1904, a two wheeled horse drawn ambulance made the round trip from Ingham to Ewan via Jacobsen’s Track in thirty-six hours, including twelve hours for the horses to rest at Pappin’s Miner’s Rest Hotel at the foot of the range. The patient who was later diagnosed with sciatica must surely have suffered greatly as the litter bounced its way over the rough tracks. (Herbert River Express, 23 November 1982)

With the rainfall then being experienced, many miners had permanent water in the ranges, a boon during most of the year. (Cameron 1901, p. 2) By damming small, fast flowing creeks and channelling the water through races, miners could carry on sluicing operations single-handed. Johnstone was working this way when visited by government geologist Saint-Smith in 1916. Another family of neighbours, the Gards, was using a small waterwheel was used to power a two-head battery on one such small creek known as The Spec. (Brown 1961, Letter from previous owner of Gards’ Battery) Accessing water in the rainforest was not often a problem for miners working there, but often there was too much rain, in direct contrast to the annual shut-down that occurred each Dry season farther west. (Annual Report of the Department of Mines 1894, pp. 105-106) In 1901, Arthur Benham sold the Midnight Queen, a reef tin claim at the head of Saltwater Creek, to Charles Edward and Samuel James Allen. (Department of Mines Registration of Claims 1 to 459; Annual Report 1902, p. 84) Arthur had been forced to apply to the Department for an exemption from work on this lease, citing

The heavy rain causing too much water to contend with and therefore I am unable to work the ground. (Digweed & Hammond, 1986, p. 109)

Benham’s tunnels, dug in an attempt to drain off water, could be located in the early 1980s by the collapsed air pipes. (Brown, 28 July 1984, Interview) I have not been out round Mount Spec myself recently, but I have no reason to believe they are not still discernible. Wilf Karnoll should know their locations.

During the Wet season, torrential downpours could also destroy stockpiles of ore set aside for crushing or washing. Unscrupulous neighbours could also make use of sudden downpours, as Fred Benham’s son Alfred related in 1980:

One funny incident happened while we had the store at Prospector’s Creek [on Benham’s Track between today’s Paluma Dam and Hidden Valley]. Dad used to do tin scratching when he had time and one year he stacked a lot of dirt ready for the wet season. At this time he did his own packing, taking delivery in Ingham. On one trip he went down for goods and it rained inches and all creeks were bankers. It was over a week before we could get home and the old boy was worried about his stacked dirt getting washed away — tin and all. When we got home he unloaded the packs, got on his horse and tore over to the gully, only to find someone had made good use of the rain and had washed all his stacked dirt and taken the tin. Away he went to find out who might have found such a good patch. Tent poles were all that was left of one bloke’s camp so he went over to Bosworth’s Store at Hidden Valley and found out that the chap had sold the tin and “done a bunk”, leaving us with a store bill of around nine quid. The old boy could not do anything about it and it was a long time before he could see the funny side of the incident. (North Queensland Register 12 January 1980; Annual Report of the Department of Mines 1896, p. 110)

Biographical Sketches

I am indebted to Lee Digweed and Marilyn for much of the information in the short biographical sketches of each of the six siblings who spent time in the Mount Spec area.

Frederick James Benham was the first child born to George and Sarah Benham. As a young man, he was ill with ulcerated lungs and was advised to take a sea voyage, which he did, sailing to America and back again. Perhaps this gave him the travel bug, for he sailed to Townsville in 1883 at the age of twenty-one. Travelling with him were his younger sister Emily and brother Arthur. Fred spent most of his life in North Queensland, working as a labourer, explorer, prospector and miner. Fred was with Arthur and Edwin when they found tin at Cloudy Creek and Ewan. Fred married Annie Haskell in 1899. Their first child was born in Townsville in 1900 but did not survive. Their second child was born in 1901. Soon after, Fred and Annie left Townsville to set up a store at Cloudy Clearing. From there, they moved the store to the diggings at Mount Spec. Their last child was a girl, born in Townsville in 1907. Fred continued his interest in mining, sharing claims with other miners as well as his brothers. The store closed during a severe drought that hindered mining, forcing Annie to travel out west as a hotel cook. Fred stayed tin scratching but strained his heart lifting the heavy bags of tin. In 1918, Fred was admitted to Ingham Hospital and Annie returned to care for him at their house on Francis Creek Road near Ingham. Fred died in 1919 aged fifty-seven and is buried in the Old Ingham Cemetery.

Emily Benham was born in 1863 and was nineteen in 1883 when she sailed with her two brothers for Townsville. One week after her arrival in Townsville, Emily was taken on as a servant at the Orphanage. She worked there for two months in charge of thirty children, before taking a position at the Seaforth Plantation in the Burdekin. There she met her future husband, Arthur Dyer. They married in 1884 and worked on stations out west as a “Married Couple”. At some stage, they came back to the coast and Arthur went into tin mining with his brothers-in-law. Their first child was born at Ewan in 1886. Two years later, they were in Brisbane, where they stayed for four years. A son was born there but died young. A daughter was born later that same year. Another son was born in Brisbane but died on their return to Townsville in 1893. They moved back to Cloudy Clearing and built their hut near Arthur’s. The creek behind the huts (now Benham’s Creek) supplied them with fresh water. In 1894, a daughter Ethel was born. Emily was assisted with this birth by her sister Ethel, who was only sixteen at the time. The creek behind the huts was first called Ethel Creek in honour of aunt and niece. In 1897, Emily was not well. Advised to take a holiday, she travelled back to England with her three young daughters and stayed some time with her mother and mother-in-law. Early in 1899, Emily and girls returned to Townsville. The family then moved to Charters Towers, where Emily ran a successful dressmaking business from home. Arthur and Emily’s only son to survive was born in 1899. Another three children were born over the next five years, but all died young. Arthur Dyer also died young in 1905, aged forty-seven, from injuries received when he was crushed between two railway wagons. Emily remarried in 1906 and moved to near Atherton with her children and new husband. Emily also died before her time in 1909 and is buried in the Atherton Cemetery.

Jesse Edward Benham was born in 1866, George and Sarah’s fourth child. He left home at eighteen and travelled alone to Townsville in 1884. Jesse’s plans of becoming a doctor were thwarted by the theft of his sea trunk from the wharf in Townsville. Jesse worked for a time at the Railways before joining his brothers at Cloudy Creek. In 1902, Jesse married Margaret Reid in Charters Towers. Jesse’s name features in the mining records of seven claims and four leases at either Hermitville (Mount Spec), Running River or Ewan. By 1904, they were living in Ewan in a bark hut with an iron roof – the first in the district. Following the birth of their first child, Jesse and Maggie travelled by coach and train to the rich tin district of Gurrumbah (Mareeba). Later, with three sons, they moved to Herberton. Jesse eventually became a cane farmer but took his older children on a camping trip through Mount Spec and Hidden Valley in 1922, following the original paths and tracks. At the time, Arthur and Edwin were working on an alluvial tin claim at Prospector’s Creek. Jesse also spent eighteen months living at Mount Spec on his retirement in 1941. (Digweed & Hammond 1986, pp.83-85) When Jesse moved from mining to the sugar industry, he managed a cane farm at Aloomba, before buying and selling farms at Gordonvale and Proserpine. The family moved to the Burdekin in search of a drier climate to mitigate the tropical ulcers on Jesse’s legs. In 1920, after the birth of their ninth child, Jesse and Maggie moved to a farm at Home Hill. In 1929, they sold this farm and bought another, also at Home Hill, where they stayed until Jesse retired in 1941. In retirement, they stayed at Mount Spec for eighteen months before moving for the last time to Charters Towers. After renting a house in town for a while, they bought a small property outside of town and grew vegetables. Jesse died in Charters Towers in 1953 and is buried there. There is another connection between Jesse Edward Benham and Paluma. Jesse and Maggie’s seventh child was Jessie Vera Benham. Jessie married John Alfred Thomson. They had six children, of whom the fifth was Keith Thomson, a long-term teacher at the Paluma Environmental Education Centre.

Edwin Henry Benham was born in 1871. At the age of fifteen, he sailed with his father, George, and sister Sarah to Brisbane in 1886. Edwin probably worked for some time in Brisbane before joining his brothers in North Queensland. Despite a heart condition and a “slight twist to one side”, probably as a result of rheumatic fever, Edwin lived in the bush for many years. Edwin never married. Edwin and Arthur were exploring the forest looking for tin and other minerals at a time when local Aboriginal groups were still living there. On one such exploration, Edwin and Arthur were caught in a storm and took shelter with the women and children at an Aboriginal camp. The men were out hunting but returned unexpectedly. Edwin and Arthur were hidden by the women overnight, leaving quickly when the men left for hunting the next morning. In 1889, Edwin, Arthur, Fred and Joseph Kenny were prospecting for tin at Prospector’s (now Hermit) Creek. They struck lode tin, a good speculation for mining. Benham family folklore claims that “it was this discovery and their remark that the lode was a good ‘Spec’ which gave the theory that the Benham brothers gave Mt. Spec its name.” (Lee Digweed and Marilyn Hammond, p. 133) Marilyn and Lee do acknowledge the other often quoted theories for the naming of Mount Spec – that it was named for a pack horse with a white blaze called ‘Old Spec’, or that the peak was named by the Captain of the Paluma working off the coast from the mid-1880s after a ship (variously a brig or a much smaller tender) that serviced the Paluma called The Spec. Edwin spent most of his life tin mining, despite the Post Office Directory of 1902 recording his and Arthur’s occupations as “Farmer, Hidden Valley”. Following ill health, Edwin moved to Charters Towers to live with his brother George and George’s wife Margaret. Edwin and Margaret did not always see eye-to-eye, so in 1936 Edwin moved to Tully to live with his niece Grace and her husband Syd Crowther for four years, before moving back to Charters Towers. This time, Edwin lived with another niece, Lavinia Paterson. Edwin then built himself a shack beside a mullock heap and between Lavinia’s and George and Margaret’s houses. Edwin was admitted to Charters Tower’s Hospital in early 1949 and died a few weeks later. Edwin is buried in an unmarked grave in the Charters Towers Cemetery.

Ethel Amy Benham was born in 1877. Ethel was only eleven when she sailed with her two older sisters, Edith and Marion, to Brisbane in 1889. Ethel suffered terribly on the journey, from seasickness and homesickness. She would not eat, cried constantly, and begged the Captain to turn the ship around and take her home to her mother. Upon arrival at Brisbane, the three sisters were met by their father and taken to Emily’s ‘house’ of corrugated iron, where a tanned Emily was cooking over an open fire. This was a shock for girls used to a comfortable life in England. Ethel attended school while she lived with Emily, helping with domestic duties after school. Ethel then travelled north with Emily and Arthur Dyer. All their worldly goods were loaded onto a horse and cart, so the adults walked most of the time. Odd jobs along the way earnt some money to keep the group going. In 1894, Ethel was midwife for Emily at the Cloudy Creek Tin Mine when Emily gave birth to a daughter named after three of her sisters – Ethel Marion Edith Dyer. Ethel then returned to Brisbane to live with Edith, helping with the dressmaking business. Ethel then found a position as a live-in domestic servant in northern New South wales, close to where her sister Marion was living. While there, Ethel became very ill and was advised to spend at least six months in North Queensland to recover. Her brothers came and collected her and took her back to Mount Spec where she once again stayed with Emily. Recovered, Ethel moved back to New South Wales, where she met and married James McAntee. Their marriage was not always a happy one. They lived in Brisbane, then on the Tweed River, then back in Brisbane. At one time, the family took up cane farming at Gundiah near Maryborough, but as James moved often seeking work, the family’s moves were numerous – at least nine times in Brisbane alone. In Sandgate Road, Ethel ran a small shop. When the last of her many children were living away from home, Ethel took a live-in position as a domestic servant with a family until retirement. Ethel died in 1972, the last of the eleven siblings who migrated to Queensland in the 1880s.

Arthur Ernest (‘Possum’) Benham is perhaps the most well-known of all the Benhams around Mount Spec. . Some details of Arthur’s life have already been mentioned above. Arthur was born in February 1868, the fifth child of George and Sarah Benham. At the age of fifteen (not eighteen, as the ship’s list records), Arthur and older siblings Fred and Emily arrived in Townsville in May 1883. These three were the first of the eleven siblings to arrive in Australia. Soon after their arrival, the two brothers, along with new shipboard friend Charles, departed for a job on the Mourilyan Tramline. Later, Arthur worked with the Kanakas on a sugar plantation on the Herbert River. In 1885, Arthur walked to Ayr then up the range to Charters Towers looking for work. He worked on the Charters Towers to Pentland rail line and as a groom for Cobb & Co. In the late 1880s, Arthur returned to the Herbert River district, where he heard of tin mining on the new Kangaroo Hills Mining Field. Brothers Fred, Jesse and Edwin joined him in the Mount Spec area, all taking up claims and leases. In 1892, Arthur, Hughie MacDonald and Unsworth flowed a tributary of the Star River and found payable tin on a creek they called Cloudy Creek. Their camp site became known as Cloudy Clearing. Arthur later built a substantial hut in Cloudy Clearing.

Sisters Emily and Ethel also lived close to Arthur in a bark hut in Cloudy Clearing. Nearby Benham’s Creek was first named Ethel Creek. Now a creek farther west is known as Ethel Creek. Ethel Falls are on this creek. At the time when Ethel assisted Emily with the birth of her daughter, they were all living at Cloudy Creek Tin Mine, Cloudy Clearing. I believe that Benham’s Creek flows into Ethel Creek just west of the township of Paluma. Others with more on-ground knowledge can confirm or dispute this. Ethel Falls on Ethel Creek probably lay on the original Benham’s Track between Cloudy Clearing and Mount Spec. Today, Ethel Falls has been incorporated into the walking track network around Paluma.

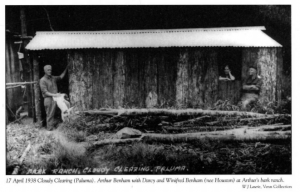

Arthur lived for sixty-five years in the Mount Spec-Paluma area, many in “the famous bark hut” in Cloudy Clearing that he made from ironbark trees cut at Running River. (Australasian Post, 8 February 1962, p.25) The campsite at Cloudy Clearing dated from Arthur and Fred’s discovery of alluvial tin at the headwaters of the Star River, though there is a possibility that the clearing was an Aboriginal camp clearing maintained by burning. The remains of Arthur’s water tank can still be seen in the gardens of Gumburu Environmental Education Centre. Interestingly, the rivets of this former ship’s tank provided industrial sculptural artist Sue Tilley with inspiration when designing and constructing her representation of the Rainbow Serpent that now slithers among the trees beside Arthur’s water tank.

Arthur’s photo appears in many articles on local tourism and history. He is remembered as something of a character, having once cleared the bar of the Hidden Valley Hotel during an altercation with another miner by riding his horse through the bar. The disagreement continued outside for several hours.(Digweed & Hammond 1986, p.104) Of all the Benham family members who passed through the Mount Spec-Paluma area, Arthur and his brother Edwin never married. They spent their whole lives living as bushmen and miners, although the 1902 Post Office directory records both their occupations as “Farmer, Hidden Valley” (Digweed & Hammond 1986, p. 134)

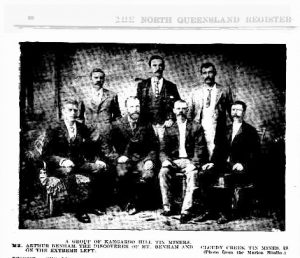

“A Group of Kangaroo Hills Miners.

Mr. Arthur Benham, the Discoverer of Mt. Benham and Cloudy Creek Tine Mines, is on the extreme left.”

(I believe that Fred is second from the right, front row and that Edwin is far right, front row)

The North Queensland Register, Monday, 11th March 1901, p. 26.

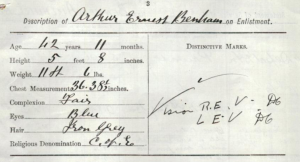

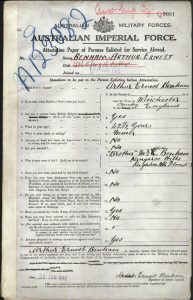

Arthur enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in January 1916 (Service No. 5659). He was one of two volunteers from Ingham, and one of twenty-three who sailed on the Wyandra to join others at the Enoggera camp. On his Attestation Paper, Arthur claimed to be nearly forty-three years of age, when in fact he was nearly forty-eight. Arthur had a habit of misrepresenting his age. On the passenger list for the Hereford, Arthur claimed to be eighteen, when in fact he was only fifteen. Despite his “Iron Grey” hair, Arthur was obviously in good shape in 1916, with a relaxed chest measurement three inches above the required thirty-three inches. By August 1916, Arthur was in Egypt on his way to England. While in England in September, Arthur went AWOL overnight and was awarded four days extra duties as punishment and forfeited a day’s pay. While serving this punishment, Arthur missed the “Defaulters’ Parade”, forfeiting another day’s pay. Within a month, Arthur was on his way to France.

Despite his apparent physical fitness, Arthur was admitted to military hospital in France in December 1916 then was transferred back to hospital in England in January 1917. He recovered and was on his way back to France by the end of February. In May, he was again admitted to hospital in France, spending two months being treated for scabies before being able to re-join his battalion in July 1917. In October 1917, Arthur spent another month in hospital in Belgium, re-joining his battalion in November 1917. In March 1918, Arthur’s fitness to continue service was assessed by the Medical Board. He obviously passed inspection, as he was sent to Normandy and spent another full year in France before returning to hospital in March 1919. Later that month, he was discharged and on his way home to Australia. By now, Arthur was fifty-one.

National Archives of Australia, B2455, Benham, A E, p.3.

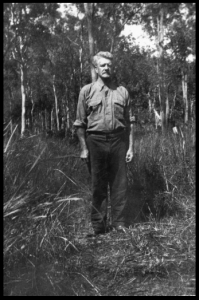

Arthur Benham

Undated, State Library of Queensland image.

National Archives of Australia, B2455, Benham, A E, p.1.

After the war, Arthur returned to Cloudy Clearing and eked out a living tin-scratching. Often, he’d go out prospecting with Jim Linton who owned the Pioneer Store in Paluma. Arthur was known to walk everywhere. He walked down his track to the Rollingstone Hotel for supplies and to spend his tin cheque. He walked from Cloudy Clearing down the Star to the Burdekin and on to Pentland to see his niece Winifred. On the way back, he walked through Homestead to Charters Towers to visit his brother George. When he’d saved enough money, Arthur holidayed by visiting his sisters in Brisbane – as well as walking to visit relatives in North Queensland.

Arthur Benham, Pioneer.

Sunday Mail, Sunday 29 May 1938, page 2.

Over sixty-five years, Arthur had registered interests in at least thirteen claims and leases. The last Benham mining lease was sold in 1945 when Arthur at the age of seventy-seven sold his lease “for the whole of Paluma” to Townsville businessman J C Butler. (Digweed & Hammond 1986, pp. 23,104; Department of Mines Transfer Certificate Alluvial Tin Claim No. 12831) This lease took in the area where Gumburu Environmental Education centre is today. The small gully under the road in to the Centre is not a natural watercourse, but the remains of Arthur’s sluicing channel at the head of Benham’s Creek. The cancellation of Arthur’s lease was urgently requested in 1939 to allow further subdivision of the new township, including setting aside 100 acres for a golf course. (Unsigned Report dated 19 January 1939, pp. 3-4) Despite cessation of mining in Cloudy Clearing, these ambitious plans never went ahead.

Arthur Benham

Undated, State Library of Queensland image.

In 1955, aged eighty-seven, Arthur became ill. His great-nephew Bill James (the son of Emily and Arthur Dyer’s first child, Arthur’s niece Winifred) travelled up to Paluma and brought Arthur down to hospital in Townsville, where he stayed some two weeks. Another niece from Charters Towers, Ivy Kammerer (sixth child of George and Margaret Benham), then took him to her home in Charters Towers to live. In July 1956, Arthur was admitted to Charters Towers Hospital two weeks before dying at age eighty-eight in August. Arthur is buried in the Charters Towers Cemetery.

Sources

Official Documents & Primary Sources

Brown, Robert

Interview with Linda Venn, 28 July 1984.

Letter to Bob Brown from Graham Heyden, Previous Owner of Gards’ Battery, 1961.

Burla, Robert

Following the Blazed Paths, 2nd Royal Queensland Regiment, Ingham, n.d., unpaged.

Letter to author, 23 April 1985.

Mountain Ramparts, 2nd Royal Queensland Regiment, Ingham, 1964, various pagings.

Notes given to Digweed and Hammond.

Department of Lands

Unsigned Report on proposed subdivision of Paluma, 19 January 1939, pp. 3-4.

Undated Map of Design for Sections V to X.

Geological Survey of Queensland Publications

Levingston, Ken, Mineral Deposits and Mines of the Townsville 1:250000 Sheet Area, North Queensland, Geological Survey of Queensland Report, No. 61, 1971

National Archives of Australia, B2455, Service Record, Benham, A E, pp. 1, 3.

Queensland Department of Mapping & Surveying, Parish of Waterview Map, January 1977.

Queensland Department of Mines

Annual Report of the Department of Mines

1883, p. 178.

1892, p. 94.

1893, p. 85.

1894, pp. 105-106.

1896, p. 110.

1901, p. 90.

1902, pp. 82, 84.

Registration of Claims 1 to 459.

Transfer Certificate Alluvial Tin Claim No. 12631.

Queensland Government Mining Journal

1901, p. 2.

1902, p. 21.

Queensland State Archives

Index to Registers of Immigrant Ships’ Arrivals 1848-1912, Series ID 13086, p. 211.

State Library of Queensland

Image of Arthur Benham, c. 1916.

Image of Arthur Benham, c. 1930.

Published Works

Digweed, Lee & Hammond, Marilyn Our Benham Children, The Summit, 1986.

Gumburu Environmental Education Centre Teachers’ Handbook, 2000.

Pike, Glenville, Over the Years – The Dalrymple Shire Past and Present, T. Willmett & Sons Pty Ltd, Townsville, 1960, p.38.

Venn, Linda The First Eighty Years, Thuringowa Central, Thuringowa City Council, 2002.

Newspapers

Australasian Post, 8 February 1962, p. 25.

Herbert River Express,

18 November 1982

20 November 1982

23 November 1982

Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser,

Tuesday 8 March 1870, p. 4.

North Queensland Herald, 12 April 1902.

North Queensland Register,

17 August 1892, p. 1.

11 December 1899, p. 1.

11 March 1901, p. 26.

12 January 1980.

20 September 1980.

Queenslander, 26 September 1891.

Sunday Mail, 29 May 1938, p. 2.

Townsville Daily Bulletin, 1 January 1935, p. 9.

Websites

Benham, Arthur Ernest, Service Record, https://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/SearchNRetrieve/Interface/ViewImage.aspx?B=3071959

History of Paluma, Mount Spec, https://www.gumburu.tsv.catholic.edu.au/history/our-history/

Venn, Linda The First Eighty Years, Townsville City Council, https://www.townsville.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/5374/Paluma-The-First-Eighty-Years_web.pdf.